Tagging Whale Sharks in Galapagos, with Sofia Green

Sofia Green, from The Galapagos Whale Shark Project, has recently completed her MSc thesis on tracking whale sharks. I talked to her while she was back at home base in Quito, Ecuador, after another stint in the Galapagos Islands. SJP

How Sofia started work in the Galapagos

I'm from Quito, but my life has always been involved with the Galapagos. My parents both lived there and still work there. I grew up moving between Quito and the Galapagos. I decided to study marine biology, and I've been working as a researcher with the Galapagos Whale Shark Project since 2017. Each year, we've done annual research expeditions to the far northern islands, Darwin and Wolf, to study the whale sharks that swim past.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve also been doing my Master's degree in Portugal. I used the data that we had from satellite tag deployments to look at the movements of whale sharks from the Galapagos and through the eastern tropical Pacific. I was analyzing where they spend their time, how deep they're diving, and working out what influences their movements and diving behaviors.

Sofia deploying a fin-mounted satellite tag

Whale sharks in the Galapagos

Whale sharks are seen throughout the Galapagos archipelago, occasionally, but they're most common up at Darwin and Wolf. They're usually seen up there during the cool season in the Galapagos. The ocean up north is much warmer than around the central islands, where the water temperature is 17–21ºC, and the western islands where it's even colder, often 12–18ºC at the surface. In the far north, the sharks get to stay at a comfortable temperature but they're still close to the coldwater front, where there’s lots of food. That's what they like, warm water and food.

The remains of Darwin’s Arch, with Darwin Island in the background. Photo: Jonathan Green.

Darwin Island is one of the most beautiful, most spectacular dive sites in the world, but the conditions there can be tough, with strong currents and surge. During our research trips we spend a couple of weeks there, diving three times a day, and on each dive we wait for a whale shark to pass by so we can satellite tag them, take photo-identification images, or collect blood samples.

To set the scene, we all dive down on scuba. Everyone positions themselves along a natural rock platform, so that as a team we're spread out a bit. We'll be sitting there, waiting for this giant fish to appear, rotating to do 360º scans of the area, then out of nowhere these giant sharks just appear in front of you. You'd think you'd see them approaching, but they just pop into view. It's funny when it's the last person in the chain that actually sees the shark, after it’s swum over everyone else's head.

When a person does spot a whale shark, they'll frantically rattle their shaker and swim towards the shark, and everyone else jumps into action too – we all look around to see who's shaking, then swim out in the same general direction, even though we often can't see the shark at that stage. If there's current, or the shark is further out, it's often the last person in the chain that has time to actually get to the shark. They look so relaxed when they're swimming, they seem so slow, but in reality, we have to swim so fast to intercept them that you're watching your air go down on your pressure gauge as you're approaching.

It makes the work a lot more exciting, for sure. We're in the middle of the ocean, the middle of nowhere really, holding onto a rock trying to spot bus-sized whale sharks, then do all this crazy stuff. It's wild when you think about it. I love it.

The whale sharks we see in the Galapagos are 99% adult females, which is the part of the population that is rarely seen anywhere else in the world. It gives us a unique opportunity to study these individuals, which are essential if we want to protect whale sharks. Adult females are the sharks that are already reproducing, so they're key to the conservation and recovery of the species. They're massive animals. The whale sharks we see tend to be 10–12 meters long, and we've seen a few that might be 13–14 meters long. They're very impressive!

Tagging giant whale sharks

The way we tag whale sharks has evolved over time. When I started with the project, in 2017, we were still using pressure guns to attach tow tags to the sharks using a little anchor dart under the skin. The tags were on this long tether, and the tag itself would float in the water slightly above the shark. The problem we had with the tow tags was low retention. We lost them very fast. Darwin is one of the sharkiest places in the ocean, and we believe that sharks and other fish, like giant trevally, were seeing this floating tag and thinking it was food. We'd tag a shark, check the attachment was strong, but then shortly afterward we'd see it again and the tag would already be gone. It was super frustrating, because these tags are expensive.

That year, 2017, was also the first year we tried using fin-mount satellite tags. We've kept working on the best way to deploy them. The tags we're using now are very slim, with a gentle clamp that holds the fin, and we attach them to the tip of the shark's dorsal fin. They're very hydrodynamic, and we get much longer retention times with them, so we've completely shifted away from tow tags now. We still get some tag loss – other sharks, like silky sharks and Galapagos sharks, will use whale sharks as a giant scratching post. One day we saw a whale shark with a fin-mount, tagged four days earlier, swim past the boat while we were having breakfast. There were some silky sharks swimming along with her giving themselves back-scratches. We saw the whale shark again on the next dive, and the tag was gone. So we still have issues with other animals dislodging the tags, and some get crushed by depth due to the pressure, but we’re definitely getting better retention times and longer tracks, which is very nice in terms of understanding the sharks’ movements.

A fin-mounted tag

That does bring me to the other problem though. Whale sharks are incredible deep-divers, the deepest diving fish. When they dive past 1,700–1,800 m, the tag gets crushed. It'd be great to be able to measure exactly how deep they dive, and the Georgia Aquarium team has been developing a 'deep tag' that can withstand the pressure at extreme depth, but the sharks exceed the limits of the available technology right now. It'll be a really interesting aspect of their behavior to study. From the tracks so far we can see that the sharks don't necessarily spend much time at depth; they dive down, hit max depth, and immediately start coming up again. It's often a stepwise movement, spending a bit of time at each depth as they move up. It might be part of their prey search strategy. The deep tags are the kind of technological advance we need to help answer this question.

Now that we're able to track the sharks for several months, we're getting much more information on their movements away from the Galapagos. A lot of them are converging off Peru between December and February. It looks like it might be an important feeding area. One of the most interesting things I picked up from my thesis research was that the sharks were diving deep while they were in the northern Galapagos area, often past 1,000 m, but they stayed a lot shallower while they were off Peru, never diving past 300 m. They're spending their time at the surface there, probably feeding. There are lots of plankton at the surface off Peru, so perhaps they don't need to dive so deep to find food.

Recruiting the dive community

Satellite tags are great, but they stay on for months, not years. The project in Galapagos started a decade ago, and we've been collecting photo-identifications of the sharks as a tracking tool over that time. Some photos go back 13–14 years. The sharks do seem to move past Darwin Island quite fast, but we're starting to get more re-sightings now, up to 12 years apart so far. It's great to see that these sharks do return to Darwin. The photo-IDs can add to the tracks we start with the satellite tags, even if the sharks don’t come back for years.

A lot of dive guides are collaborating with the project now, which is fantastic. Before, we'd only get IDs from the sharks we'd see on our expeditions. Now, we're getting in many more photos, and we're up to almost 700 identified whale sharks from the archipelago. That's what is helping us to get these re-sightings across years. I got super excited last week when there was a re-sighting of one of the first whale sharks I ever say, from the trip we did together in 2017. That shark returned to Darwin in 2020, then again in 2021. Thanks to the dive guides and their guests, we were able to see that this shark has come back several times now.

A resighted whale shark on the sharkbook.ai interface

I've started working with a company called Galapagos Shark Diving, where I act as a trip leader and talk with the divers that join me about what's going on in the Galapagos Marine Reserve. People love the diving, and they want to understand more about the area, what the real problems are, and how they can personally make a difference. It's nice to be able to do this kind of outreach, to meet more people, and to provide a trip that combines something as beautiful as diving with the conservation of an endangered species.

It's funny because people are often like, oh, you must be bored of whale shark photos. No way! For me, every single one of those whale sharks has a name. Every encounter with a whale shark is unique. Diving with guests, it's fantastic to see somebody that's dreamed of seeing a whale shark when they have their first experience. The excitement when they come out of the ocean, it's just, oh my gosh, it moves me. I love it. I love being a part of that. I get it, too. Every time I see a whale shark, I'm still impressed. I don't think it will ever become normal to me.

Tagging whale sharks for conservation

We've recorded some fantastic tracks over the past few years, and they’re informing some great conservation initiatives, both in the Galapagos and internationally. Our work has shown that the area around the Galapagos is really important to the species – it's one of the only places where adult females are seen. There's an initiative underway to expand the Galapagos Marine Reserve, to help protect sharks when they leave the Reserve. They're well-protected when they're inside that area, but there are a lot of human threats once they leave. We have intense fishing pressure all around the Reserve, especially during the time of the year whale sharks are present, because it's such a productive area. Giant fishing fleets are waiting to catch sharks when they leave the protected area.

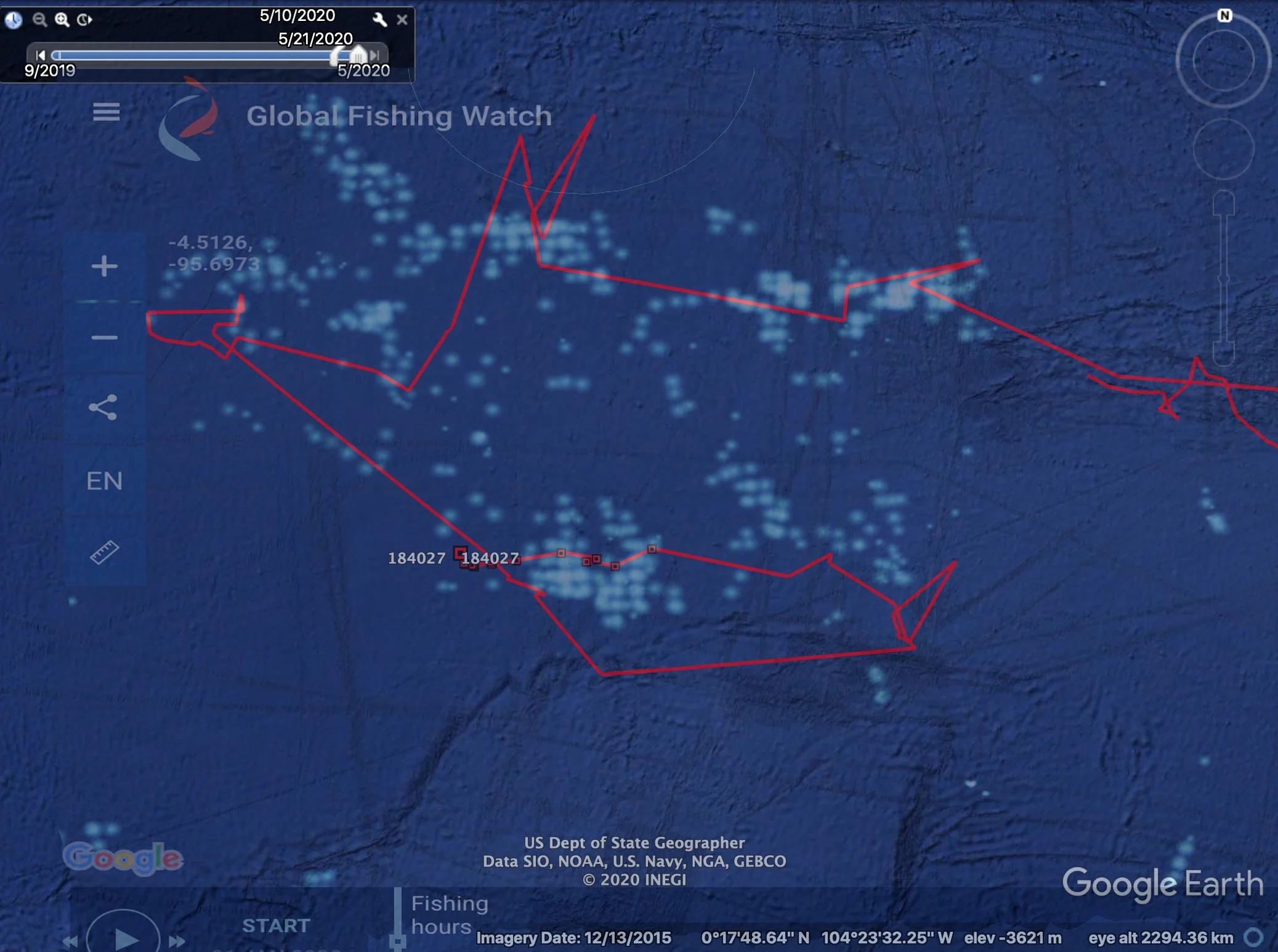

Hope’s track between September 2019 and May 2020, superimposed on Global Fishing Watch data (fishing vessels in light blue)

We were sharing a track online of one particular whale shark, Hope, as she moved away from the Galapagos and seemed to be looping back. Then, she suddenly stopped transmitting. We'll never know for sure what happened, but the tag data suggested she was caught by a fishing vessel. When we reported that, it was local news. Then, suddenly, it seemed to catch people's attention. There was this shark that lots of people had been tracking on social media, they knew what she looked like from our photos, they knew her story. Then, she suddenly went dark, and it was like, boom, we've just lost this whale shark we cared about, that we had a connection to. It became international news, and China had to recall some of their fishing fleet. It was a huge deal. It's so important to tell these sharks’ stories, because Hope’s story is representative of so many endangered species that lose their lives this way, every single day. She wasn't just representing herself, she was representing all of them. So the idea is to expand the marine protected area around the Galapagos to give these animals a chance.

Hope’s last photo, just after she was tagged in 2019

We also had one whale shark that moved from Darwin Island to Cocos Island, off Costa Rica, last year. We already knew that the area between these islands, both World Heritage Areas, was an important swimway for other sharks, sea turtles, and marine mammals. Having a direct track connecting these two protected areas helps to show the importance of protecting that movement corridor, and turning it into a multinational protected area. It would protect the whale sharks, but also all these other species.

Whale sharks are a great ambassador for other endangered marine wildlife. I'm whale shark obsessed. It's easy to love these creatures. But it's nice to know that the work we're doing is not just to protect whale sharks, it's to protect the oceans. It's to protect the future of our own species.