Third Manta Ray Species Discovered in Atlantic Ocean

Marine Megafauna Foundation celebrates formal description of new Atlantic manta ray species, validating predictions by renowned manta ray expert Dr. Andrea Marshall

Florida Manta Project founder, Jessica Pate, dives to get an identification photo of the manta’s unique belly spot pattern. Photo: Bryant Turffs

WEST PALM BEACH, FL – The Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF) today celebrates the discovery of the third manta ray species, Mobula yarae, found exclusively in Atlantic Ocean waters. Published in Environmental Biology of Fishes, the new manta species discovery represents the culmination of a 15-year scientific journey that began with observations by MMF co-founder Dr. Andrea Marshall in 2009.

Dr. Marshall, who revolutionized manta ray science by splitting what was thought to be one manta ray species into two distinct species in 2009, predicted in that same landmark paper that a third manta ray species existed in the Atlantic Ocean.

Dr Andrea Marshall processing data in Tofo, Mozambique. Dr Marshall pioneered manta research and was the first person in the world to be awarded a PhD on manta rays

The confidence behind that prediction came from years of intensive study—including countless hours spent hand drawing individual manta rays from her own underwater photographs to hone her observation skills and understand their morphology in minute detail. "It had taken me 6 years to differentiate the first two species and I knew them inside out at this stage." So when she finally encountered the third species in Mexican waters, the recognition was immediate: "This manta didn't look like either of them."

Juvenile female manta ray in the shallow nearshore waters of south Florida. Photo: Bryant Turffs

The new Atlantic manta ray species, named Mobula yarae after Yara—a water spirit from Indigenous Brazilian mythology—inhabits tropical and subtropical waters from the eastern United States to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Mobula yarae becomes the third formally recognized manta ray species worldwide, joining the reef manta (Mobula alfredi) and giant oceanic manta (Mobula birostris).

Dr. Marshall had been working with international collaborators to publish a formal description of this new species when she suffered a severe brain aneurysm and stroke in early 2024, following which she remains on long-term medical leave. The formal description was completed by an international research team led by Brazilian researcher Nayara Bucair from the University of São Paulo, with MMF's Jessica Pate carrying forward the collaboration and providing Andrea’s data and observations.

"This discovery confirms what Andrea has long been working on," said Dr. Simon Pierce, MMF Executive Director and co-founder. "Andrea's 2009 taxonomic work on manta species flagged the likely existence of a third Atlantic manta species based on careful field observations, and this formal description brings that work to completion."

The Discovery

Marine Megafauna Foundation co-founder, Dr Andrea Marshall, first realized there might be a third species of manta ray while diving off the Yucatan in Mexico. Photo: Janneman Conradie

In a 2022 social media post, Dr. Marshall reflected on the extraordinary journey that led to discovering this third manta species:

"In 2009, it was one of the largest species discoveries of the last 50 years. It was huge for me as an early career scientist and such a privilege to go through every step of the process. Did I ever expect to do something like that again? Hell no. Not a chance. So it was one of the shocks of my life to jump into the warm waters off the Yucatán in Mexico about a year later and come face to face with what I instantly knew was a third species of manta ray."

The recognition was immediate, but convincing others would prove challenging. "It had been pretty shocking to everyone that there were two species of manta ray and suddenly I had to argue that there were three. To be honest, I was not sure if anyone would believe me. But there was never a doubt in my mind. That confidence came from the fact that it had taken me six years to differentiate the first two species and I knew them inside out at this stage. This manta didn't look like either of them."

Dr Andrea Marshall discovered the third manta species after diving off the Yucatan in Mexico. Photo: Janneman Conradie

For Dr. Marshall, the discovery represented proof that the age of discovery continues. "Kids often ask me if, in this day and age, there is really anything left to discover. I always laugh and end up telling my story because I am living proof that there is. The only barrier we face is being close-minded and assuming we know it all, when in fact we have barely scratched the surface..."

How to Tell The Three Manta Ray Species Apart

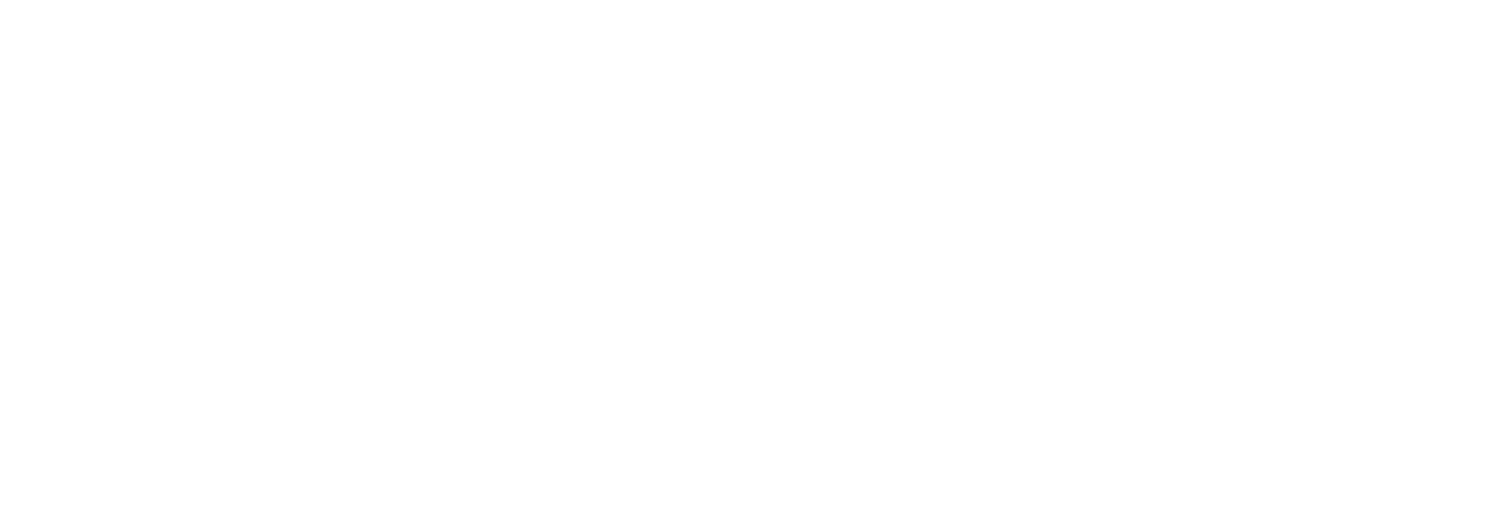

Distinct colouration of manta ray species. Dorsal and ventral colouration pattern of Mobula birostris (a, d) Mobula alfredi (b, e) and Mobula yarae sp. nov. (c, f. ) Photos: Leo Francini a; Guy Stevens | Manta Trust b, e; Rawany Porfilho c; Mauricio Andrade d; and Nayara Bucair f

Mobula yarae shares many characteristics with both existing manta species, which explains why it remained formally unrecognized for so long. Here's how to distinguish the three species:

The Atlantic manta ray displays a mix of traits from both known manta species. From above, the black dorsal coloration and pectoral fin shape look like a giant oceanic manta (M. birostris). On the belly, the lighter face and spot patterns resemble a reef manta (M. alfredi).

The key distinguishing features:

Shoulder patches: M. yarae has distinctive "V-shaped" white shoulder patches, unlike the "T-shaped" patches in M. birostris

Face coloration: Lighter coloration around the mouth and eyes compared to the darker faces of giant mantas

Ventral markings: Dark spots typically confined to the abdominal region, not extending between the gills as in reef mantas

Size: Can grow 5-6 meters like giant mantas, though many observed individuals are smaller juveniles, and often found in coastal waters like reef mantas

For years, researchers used the designation "Mobula cf. birostris" in scientific literature—essentially meaning "similar to birostris"—acknowledging the close resemblance while noting potential differences.

"It's a classic case where genetic analysis was needed to confirm what careful morphological observation suggested," explained Pate. "The differences are consistent once you know what to look for, but they're subtle enough that definitive identification requires expertise."

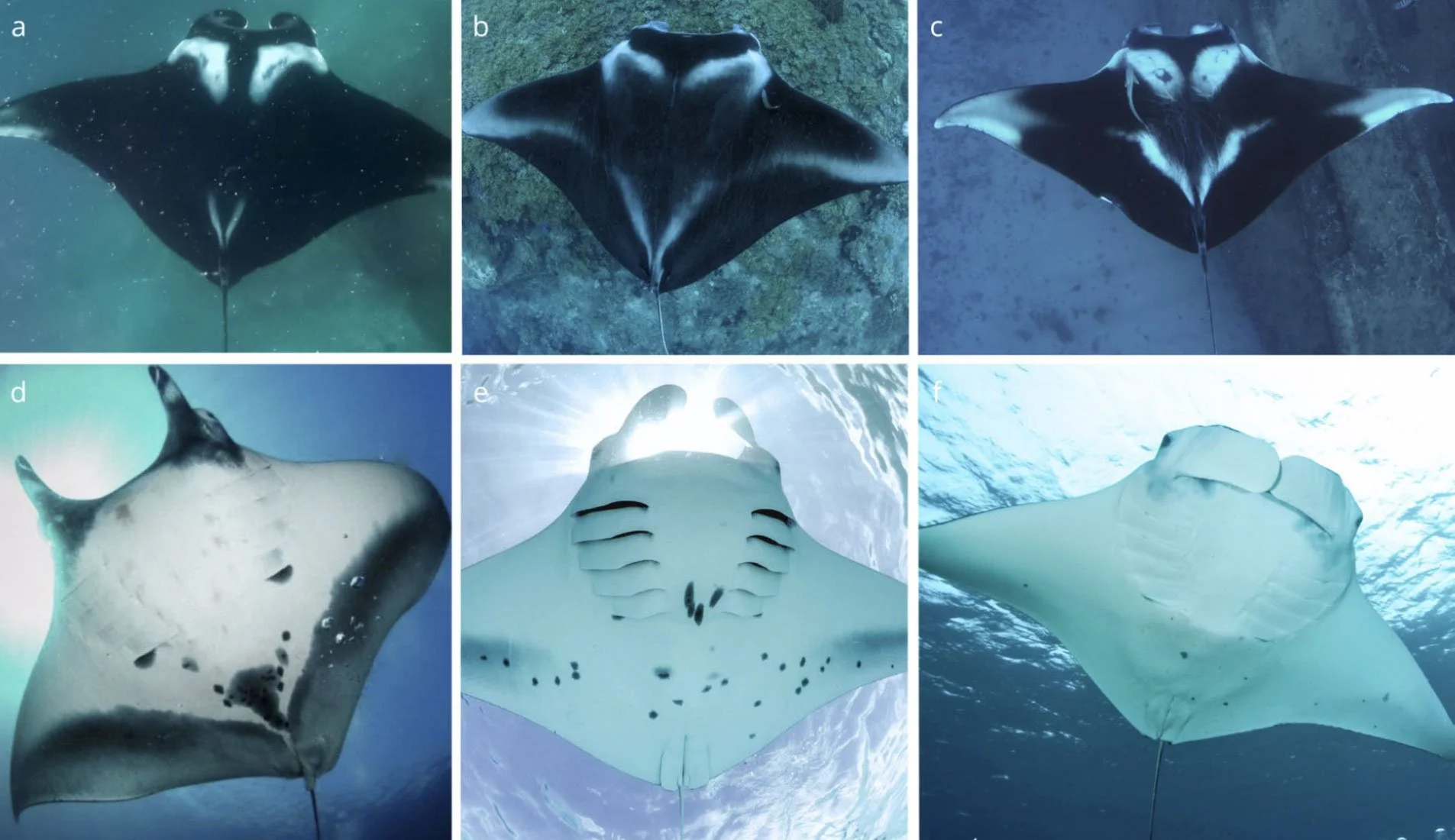

Colour morphs variation on the regular spectrum of Mobula yarae sp. nov. Dorsal (column a and b) and ventral (column c and d) colouration pattern disparity. Photo credits/sources: Projeto Mantas do Brasil and Marine Megafauna Foundation database

Manta Ray In Brazil Confirms Broader Distribution

Following her recognition of the third species in Mexican waters, Dr. Marshall expanded her investigation to other Atlantic locations. Between 2009 and 2010, she traveled to Brazil during winter months to collaborate with researcher Ana Paula Balboni Coelho, who had been collecting manta ray photo-identifications in Brazilian waters since 2001 as part of what became the Mantas do Brasil Project.

The collaboration proved immediately fruitful. "I showed Andrea the footage of a female I had rescued from a fishery net" Ana Paula recalled. "Andrea looked at me and said: 'Ana Paula, this is NOT A BIROSTRIS!' I thought she was mad."

But Marshall's trained eye could spot the distinctive features. "We analyzed the images, color, pattern, size, and she was sure it was not birostris. It was mind blowing," Ana Paula remembered.

This confirmation that the third species occurred in Brazilian waters as well as Mexico suggested a much broader Atlantic distribution than initially suspected. Ana Paula spent years gathering additional scientific evidence, eventually coordinating the first manta ray necropsy in Brazil in collaboration with Andrea.

A Breakthrough in Florida

The pivotal moment came in July 2017, when Jessica Pate, then in only her second year leading MMF's Florida Manta Project research program, received an urgent call about a dead manta ray found off Pompano Beach, Florida.

The Florida specimen was exactly what Marshall had been searching for. The Atlantic species had proved uniquely challenging to study - unlike the first two manta species, there were no existing fisheries to provide the essential specimen that researchers could use as a type specimen to describe a species. For eight years, teams had conducted fieldwork across Mexico, Brazil, and Florida, documenting the animals through photography and underwater observation.

But when Jessica received that call about a naturally deceased manta found off Florida's coast, it represented a rare scientific opportunity. The intact specimen could finally provide the detailed morphological measurements and genetic samples needed to complete the formal species description.

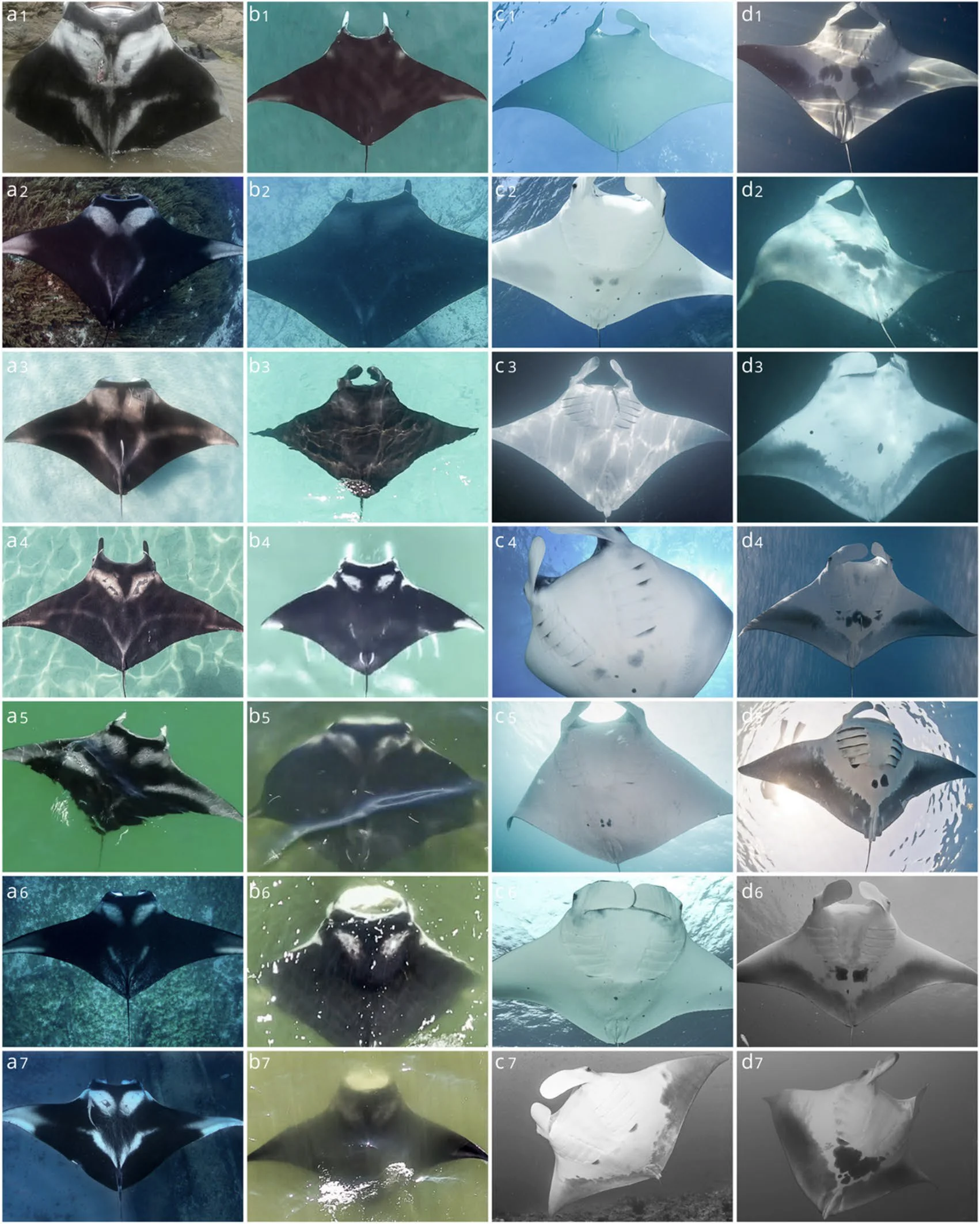

Researchers, Jessica Pate and Sarah Hoffman, collect important measurements for the manta ray that would serve as the type specimen for the description of the new species. Photo: Bethany Augliere

"I quickly called Andrea and she said, ‘buckle up this is going to be one of the most important days of your career,'” recalled Pate. "Andrea had been waiting 8 years for a specimen of the third species that could be used as a type specimen to describe the new species."

Despite being what she calls "a baby manta scientist back then," Pate understood the significance. The 8-foot (2.4-meter) juvenile female specimen was intact, unscarred, and still fresh—a rare opportunity that required immediate action.

"I pleaded with the researchers not to cut up the manta ray for samples and raced down to Pompano Beach," Pate said. "There were many hours of taking measurements and making phone calls to figure out where to store an 8-foot manta ray. Andrea guided me through the entire process from Mozambique. Even from across the world, she knew exactly what needed to be done. I was nervous—but Andrea walked me through every step. Securing and preserving that specimen was crucial to proving what Andrea had suspected all along."

Florida Manta Project founder, Jessica Pate, examines the tooth band of the manta ray specimen, tooth counts being one of the distinguishing features of the species. Manta rays have a band of thousands of small knobby teeth on their lower jaw and no teeth on their upper jaw. Photo: Bethany Augliere

Working with Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, which made space in their whale freezer—requiring the arrangement of other marine specimens to accommodate the manta—Pate and her team loaded the specimen into a borrowed truck (which still bears a scratch from that day) and drove two hours down Interstate 95 to preserve this crucial piece of scientific history.

Researchers load the manta ray specimen in a truck bed for transport to Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Photo: Bethany Augliere

A Cross-Country Journey with Precious Cargo

Later, when transporting the specimen to the Smithsonian Institution, Dr. Marshall's multi-state drive hit a snag just four hours in when police pulled them over. In video footage from the incident, Marshall explained: "We just got pulled over by the cops... They wanted to actually see the manta and our permits, so we had to uncover the manta."

The team had insulated the truck "like a refrigerator" for the long journey, but after unwrapping the specimen for inspection, Marshall worried about their precious cargo. "I can actually see, there's water coming out. I can see it's leaking a bit from some of the ice we've packed around this animal. So I don't even know if this is going to work. We still have many, many states to go."

Despite the setbacks, the specimen made it safely to the Smithsonian, where it became the official holotype for the Atlantic manta, Mobula yarae.

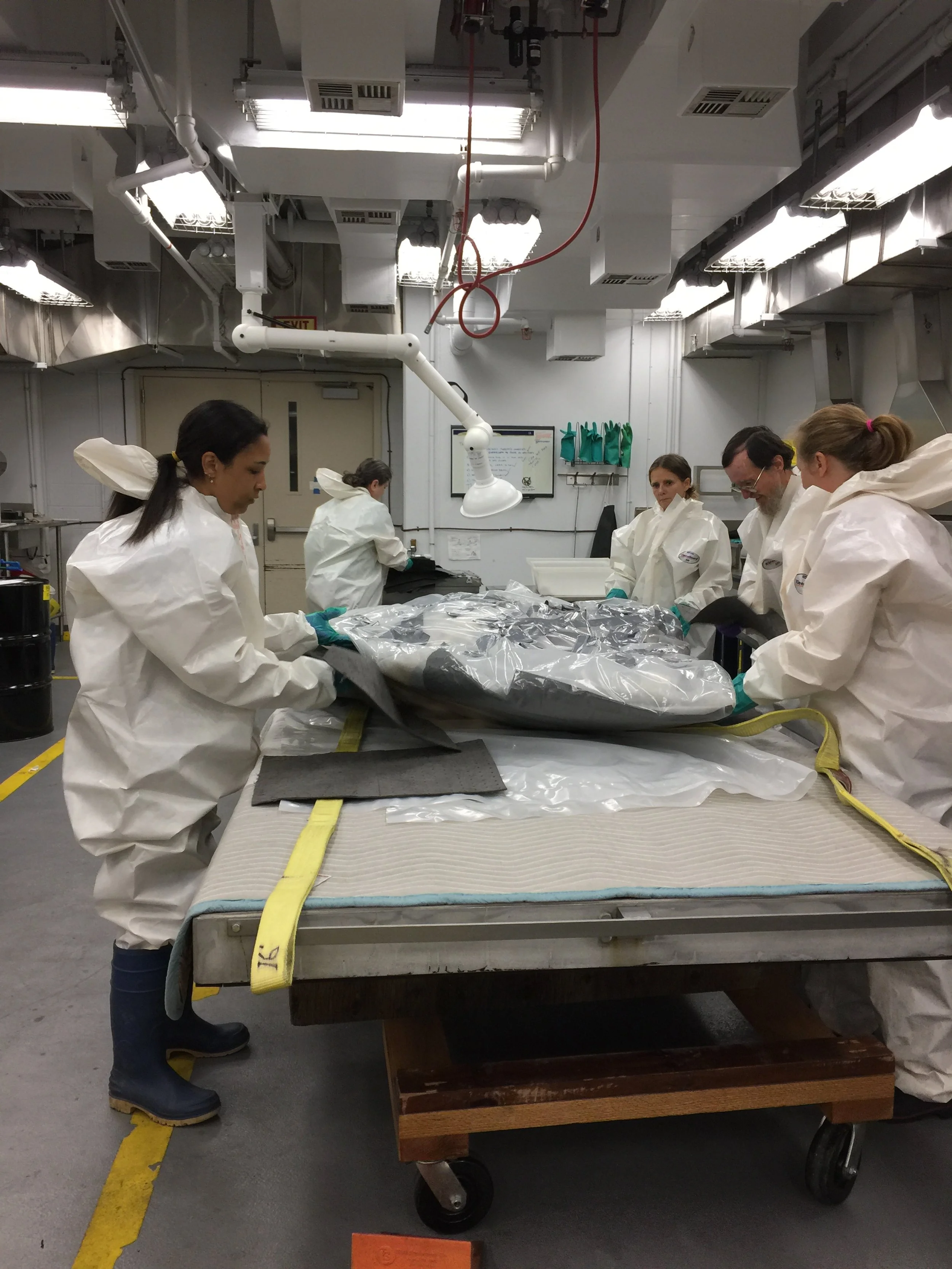

In December 2017, Andrea Marshall transported the manta ray from Florida all the way to the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) Museum Support Center in Suitland, MD. Once received NMNH staff retrieved tissues samples for deposit in our Biorepository and then the manta into frozen storage. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

After a few months left in formalin preservation to “fix” the NMNH team prepares to move the manta is moved back to our necropsy facility in order to rinse away the formalin. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

The manta is lowered into a brand new, and larger, specimen storage tank following collection of denticle samples. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution

Watching Evolution in Real Time

The discovery of the Atlantic manta offers scientists a rare glimpse into evolution in action. As one of the most recently evolved lineages of sharks and rays, manta rays provide a window into ongoing speciation, with genetic evidence suggesting M. yarae diverged relatively recently from other manta ray species.

"We're probably still watching speciation occur!" said Pate. "This species has very recently evolved from the giant manta—it's rare to see a new species like this, and even rarer to watch the process behind it."

The relatively recent divergence makes the Mobula yarae particularly valuable for understanding how large marine species adapt and evolve. The species represents evolution in motion, providing insights into the processes that drive biodiversity in marine environments.

New Species Under Threat from Boats and Fishing Nets

Manta rays in Florida are often seen with injuries from boat strikes. Here you can see two boats pass closely to a manta at the surface. Photo: Bryant Turffs

Unlike their wide-ranging relatives in the Indo-Pacific, Mobula yarae appears to have a more restricted distribution in the western Atlantic Ocean, from the eastern United States through the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea to coastal Brazil. The Atlantic manta ray species has been documented in both oceanic islands and archipelagos as well as coastal and estuarine regions.

This coastal preference makes the Atlantic manta ray species potentially more vulnerable to human impacts than their oceanic relatives. The manta ray species is caught as bycatch in gillnets, trawls, and other fishing gear throughout its range, with some specimens recovered from artisanal fisheries in Brazil.

MMF's Florida manta ray research has documented boat strikes and fishing line entanglement as significant threats in Florida waters. In the Gulf of Mexico, shrimp trawling is likely a major source of mortality for this species.

A juvenile male manta ray named Crawford with fishing line tightly wrapped around his pectoral fin. Researchers were unable to remove the line and he eventually lost the tip of his fin. Photo: Bryant Turffs

"The formal recognition of Mobula yarae is crucial for manta ray conservation efforts," explained Jessica. "You can't protect what you haven't formally identified. Now that we’ve proven that this Atlantic manta ray is distinct, we can tailor our research and conservation initiatives to protect the species."

The species' restricted range, combined with documented threats throughout its habitat, suggests vulnerability to population decline. Because all currently recognized manta ray species are classified as threatened on the IUCN Red List, Mobula yarae requires immediate conservation attention.

Moving Forward with Atlantic Manta Ray Research

MMF will continue studying M. yarae populations throughout much of their range, with Pate now leading ongoing manta ray research efforts in Florida and working with international partners to better understand the species' biology, ecology, and conservation needs. Current Atlantic manta ray research includes satellite tagging studies in Florida waters and ongoing population monitoring at key sites in Mexico.

"This formal recognition is just the beginning," said Pate. "In Florida, we're seeing these manta rays in areas with heavy boat traffic and coastal development. Understanding their habitat needs and movement patterns is crucial for their protection."

The organization also plans to work with range countries to develop appropriate conservation measures for the newly recognized Atlantic manta ray species, building on MMF's track record of science-based conservation advocacy.

Future research priorities include population assessment across the species' range, movement pattern studies using satellite telemetry, habitat use characterization, and threat assessment in key areas.

END

____

About the Marine Megafauna Foundation

Founded in 2012, the Marine Megafauna Foundation is a global non-profit organization dedicated to the research and conservation of threatened marine megafauna. Operating through a distributed network model with teams across the Americas, Western Indian Ocean, and Asia-Pacific regions, MMF conducts pioneering research that supports community education and sustainable conservation solutions for ocean giants including manta rays, whale sharks, and other threatened species.

MMF's work follows a proven six-phase Conservation Blueprint that systematically identifies critical habitats, analyzes threats, implements targeted conservation measures, secures permanent protection, builds sustainable management capacity, and expands protection networks. This evidence-based approach has secured international and national protections for manta rays and whale sharks in multiple countries, established new marine protected areas in critical habitats, and developed innovative community-based conservation programs.

With over 100 peer-reviewed scientific papers and a track record of pioneering research techniques including AI-enhanced photo-identification and satellite telemetry, MMF has fundamentally changed scientific understanding of marine megafauna. The organization's commitment to local capacity building is exemplified by programs like the UNESCO-recognized Ocean Guardians initiative in Mozambique, a UNESCO Green Citizens Project that has reached over 3,800 children across ten schools, and the Coral Reef Club, which provides pathways from education to professional conservation careers. Community scientist initiatives engage over 10,000 contributors in research efforts worldwide.

Despite maintaining exceptional financial efficiency—with 82% of expenditure going directly to research and conservation activities—MMF has achieved conservation victories that organizations with far larger budgets struggle to match, demonstrating the power of strategic, science-based conservation in the world's most important marine biodiversity hotspots.